Many marketers are quick to prescribe to their clients a laundry list of tactics that may or may not be based on some sort of overall strategy. The client usually comes back with “how much”, and the marketer usually responds with a la carte pricing as if you were buying a car. Then the client chooses leather seats, moon roof, and keyless entry, but holds off on the special paint for now. Sound familiar?

What’s largely missing from this exchange is what I would consider the most important question the marketer could ask their client: what is the lifetime value of your customer?

The lifetime what?

The lifetime value (LTV) of your customer is loosely defined as the net dollars a customer contributes over their life as a customer. It is important because you will need to know this in order to properly assess what you will spend on all of the laundry listed items above.

Lifetime Value (LTV) = Total Customer Revenue – Total Customer Costs

Example: let’s assume that a customer generates $1,000 in LTV, or net contribution margin, during their lifetime. Knowing this, you wouldn’t spend $1,000 to acquire a new customer, right? Of course not. You should earmark about 10%, or $100 towards acquisition cost.

My colleague Steve Patti found a really good LTV calculator, compliments of the Harvard Business School. In there, there is an excellent graphic describing the impact of customer retention on profits, which basically illustrates the simple principal that the longer a customer stays with you, the more profit they generate. For those of you who are finance geeks, a more complicated formula to calculate LTV would include things like net present value, or the discount rate, based on the company’s cost of capital, or things like churn rate (which vary across the lifetime of a customer).

Some examples of revenue are obviously new purchases, but also warranty upgrades, accessories, license renewals, etc. Some examples of customer costs could be tech support, service and warranty claims. This will easily get into a complex web of customer segmentation, which is OK, you need that and we will look at that here in a bit. You could even break down your customer lifetime values by original marketing channel for additional insight (such as paid search, direct mail, broadcast, etc).

Not All Customers Are Created Equal

Another mistake marketers make is assuming that all of your customers are exactly the same in terms of revenue per customer, cost per aquisition and other metrics. This is wrong. Let me illustrate:

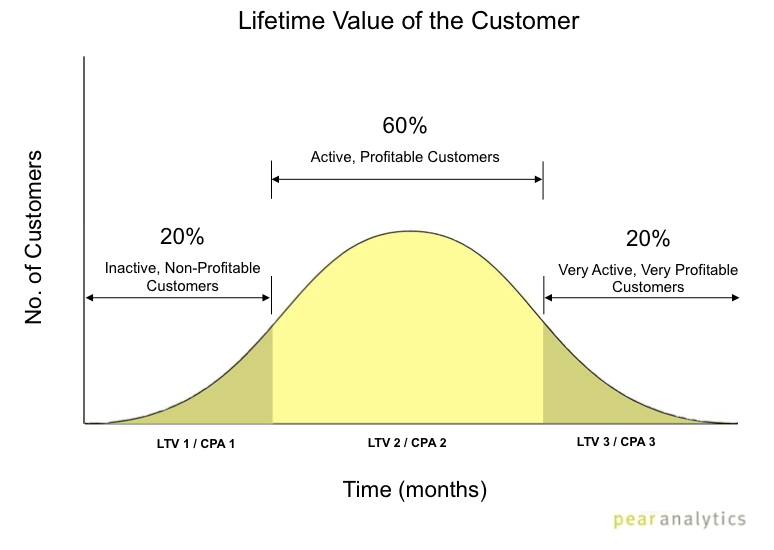

For many, the majority of their customers are going to fall in the middle of being fairly active and profitable customers, while about 20% are relativly inactive (or customers who use up a lot of support, rarely upgrade or buy peripheral products), and another 20% who are highly active. The 20% of highly active customers are really your “brand evangelists”. These are folks who refer a lot of new customers, upgrade frequently, and generally purchase on any cross-sell opportunity becasue they truly love your product or service.

What I want you to take away form this illustration is that each segment of customer has a different lifetime value (LTV) and cost per acquisition (CPA), and so how we market to them and how much to spend should be different.

Now that you see this illustration, should you spend the same amount of money marketing to the right side of this curve, as you would to the left? An example is your local cable or phone company. You see all kinds of introductory offers (with high cost per acquisition) to lure in a new customer, but there is little for the customer who has been there 5 years. I’ve yet to receive any kind of promo from my cable company as an 8+ year customer – not even a free movie, or a DVR box upgrade. How much is that really gong to cost them? Not nearly as much as it would to lure me in with a “6 months free cable” offer, which is why high utilization customers (right side of model) have a much lower cost per aquisition on additional products and/or services. Let’s not even mention all the people I would tell through all the social networks about how well they treated me, potentially adding several more new customers. Instead, I am tempted to take the competitors introductory offers. This kind of marketing does not create longevity through value, but fickleness through price.

So the only loyalty and retention marketing that is done is when you call to cancel, and they send you over the “retention” department as a last resort to get you to stay. Why does it have to come down to that? Now I tell all my friends that all they have to do to lower their bill is to call and complain about it. My colleague Alan Weinkrantz did that, and it got him a segment on Good Morning America, and now the whole country is doing it – at the same time. So let me close this “rant” by saying this type of bad marketing, similar to end of the month price reductions, or end of the year clearance sales, only conditions the consumer to react to your brand when it’s convenient for them, not when it’s convenient for you (the marketer).

The Relationship Between Lifetime Value and Cost Per Acquisition

Back to the chart above, we see that as we move to the right, our lifetime value increases, as our cost per aquisition decreases. This means that they are inversely proportional to one another. The reason is that as a customer moves into a “high utilization” stage, you need to do little and spend little to get them to purchase, or to refer new customers. This is where well-designed referral programs do very well. For the most part, they require little resources and the rewards create high value to the customer, but are low cost to the company. As marketers, we want to do everything possible to move customers from the low lifetime value, high cost per acquisition over to the high lifetime value, low cost per acquisition.

Some Examples of Lifetime Value

1. Diapers – as a father of 2 children now, I have purchased lots of diapers over the years. You could assume the tenure of a customer (in this case a baby) would be about 2 to 2.5 years, and an average spend of $50-75 per month on the diapers and accompanying wipes, perhaps the direct lifetime value is around $1,500 – $2,000. There is referent value as well, where I might tell other parents about how well Huggies is in stopping leaks, versus Pampers, etc. This is called indirect lifetime value. What could this be worth?

2. New Vehicles – it is estimated that a person will buy 7 cars over their lifetime. If the average car sells for $30,000, with upgrades, interest on the note, and service, you could spend upwards of about $45,000 per vehicle. This is why some dealerships go out of their way to service their customers because they want them to come back for another car in 4-7 years. Just ask Carl Sewell, author of Customers For Life: How To Turn That One-Time Buyer Into a Lifetime Customer. Personally, I am on my second Audi in 10 years. My first one was great (I shouldn’t have gotten rid of it), but my second one has had two engine replacements so far. In fact, it has had so many problems that I was considering moving to Lexus or BMW, and ditching the Audi brand. The thing that is keeping me from doing that is the exceptional service I received from Cavender Audi in San Antonio. As representatives of the brand, they stood by their product, and are now up to probably $20,000 in repairs on this one car of mine. They want my business for the next 3 vehicles or more.

3. Cable Service – I mentioned that I had been a customer of the same cable company for 8 years now. However, with increased competition, bundled packaging, price-lock guarantees and more, people are becoming more fickle and moving from service provider to service provider simply becasue of price. The services offereings, packages, quality and reliability are all generally the same in the eyes of the consumer, so the common denominator becomes price and value. I think these service providers could have customers for extended periods of time if they did more on loyaly and retention (the value part), versus focusing all efforts on defection from competitors and new acquisition (the price part).

Are you measuring lifetime value of the customer?